In 1952 the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (D.S.M.) classified homosexuality as “sociopathic personality disturbance.”

Yep, experts worldwide included homosexuality in the handbook with descriptions, research, treatment, and diagnoses for mental disorders. Then, in the second edition (we are up to edition five), the experts re-classified homosexuality as a sexual deviation, stigmatizing the L.G.B.T.Q. community for deviating from what they believed, at the time, to be “normal.” (Drescher, 2009).

When I first learned of this during my studies, I was dumbfounded. I, later on, would discover many, many things throughout our scientific history that made me question how we go about our research and the implementation of treatments. Here I was, proud to be pursuing Psychology, a lifelong dream of studying the mind and brain, and suddenly I’m faced with a massive dilemma—we have outrageous points in history that have been harmful to humans, and yet, are we learning from history or repeating it?

As humans, we get things wrong, which is okay. But in our eagerness to find and introduce discoveries, there can be a lack of evidentiary support and due diligence or accountability. Because of this, there have been incredibly harmful occurrences to humanity throughout time.

An integral part of bringing balance and responsibility to science, new findings, and change is not to dismiss those who oppose or don’t jump on board too quickly. But, unfortunately, history (and even now) has persecuted people for disagreeing or showcasing other hidden or purposely left-out factors. As a result, they are outcasted, seen as “conspiracists,” mocked, or bullied into submission—and at times, stripped of their human rights.

When discoveries are harmful or “wrong,” the mistakes and poor treatment, including those who initially disagreed, can often be dismissed. A new “discovery” takes its place to rectify mishaps, but it can inflict more harm when implemented too quickly and without the humility of previous errors.

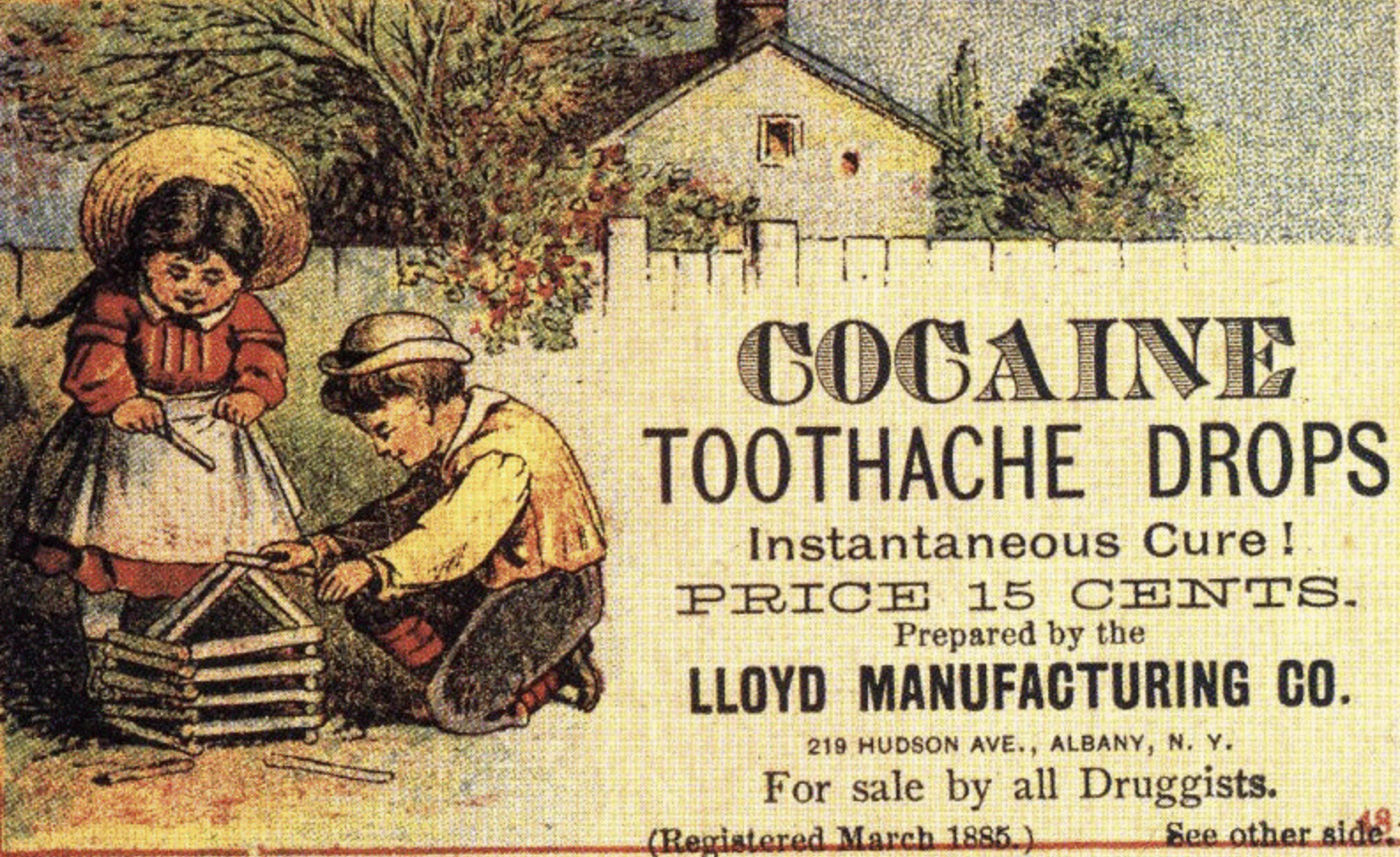

After the Civil war, veterans used morphine for pain and injuries. However, history (and current times) show that morphine and opiates, like Oxycotin, are highly addictive, leading to troubled livelihood. So, to help with morphine addiction, or as they termed it, a cure for “morphinism,” a new antidote was born. The treatment consisted of—cocaine, yes, cocaine.

Freud, a well-known physician, who’s theories constructed the entire framework of my psychology studies (and many of which have since been voided), also experimented with cocaine. He shared this “miracle drug” (in the form of Coca-Cola) with his inner circle, interested in its magical powers and promoting its excellent benefits. He also used it to help wean his friend of morphine, claiming it cured him, but it was soon discovered (and evident through the debilitation of people’s lives) that cocaine, too, was addictive—and it did not cure his friend.

The list of outrageous medical treatments and discoveries goes far beyond these examples. Let’s recall: lobotomies. (I get dizzy every time I think about it.)

Here we have it, medical and psychology professionals who, in their hast for resolution, get it wrong or act inhumanely—and in their realization, quickly endeavor to undo the damage by jumping to new conclusions, too fast, yet again.

The problem with our history and current times is not about “getting it wrong”—we all make mistakes.

Our downfall as humans, especially in science, is our hastiness to preach that we have the answer, the “miracle drug,” and discounting conversation that objects to it. Furthermore, speaking too soon about findings, or implementing treatments and ideas, without first voyaging on a long, long path of research and healthy critic, can cause further harm rather than bringing resolution.

Where is the accountability for those, who in their haste for an answer, cause harm to their fellow human? What about the populations of people forced into inhumane treatments against their free will and human rights?

Why are we so quick to dismiss people who object to findings in science, as though science is the holy grail? We see this blindness in religion too—so convinced that we are correct, and they are wrong, and yet, are not science and faith meant to be paradigms of seeking truth?

Is not the pursuit of truth the acknowledgment that we all have blind spots?

Truth requires us to look at ourselves and acknowledge our tendencies as humans to pursue our carnal drives. That is why much of religion and spirituality centers around self-control and not acting from a place of impulse, greed, or selfishness. Unfortunately, our ambitions can be shortsighted by our desire for money, power, status, fame, recognition, and feeling loved, valued, or worthy in this world.

The most significant downfall of science and discoveries is not only the mistakes (because they happen), but those driven by their own ambition, who have forfeited due diligence, proper examination over long periods, and wariness about being concrete in their findings.

We have to ask, has scientific discovery and treatment been more about them than their fellow human?

In our pursuit of truth and answers, there must be healthy criticism throughout the process so that we do not fall victim to our biases, ego tendencies, or even our fears.

We need to remain open to others’ concerns, views, and perspectives for a well-rounded dialogue—and so that we implement change from a place of integrity and safety, even if that means examining various opinions and attitudes in complete contrast and opposition to our own.

The way we demonize others who do not instantly jump on board with us and who question findings in science—especially when there is a lack of evidence and longitudinal studies—is detrimental to those discriminated against and those pushing their conclusions.

Even while studying, we were discouraged from using evidence and peer-reviewed papers without longitudinal studies, as they did not deem them as adequate evidential support for our claims. And for a good reason. A vast amount of our Psychological research is on Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic (W.E.I.R.D.) test subjects. This is hardly a depiction or reflection of the world at large.

The American Psychological Association (APA) itself discusses the oversampling of “W.E.I.R.D” samples, with 80 percent of study participants being from this sample, and only 12 percent from the world’s population—which does not accurately represent human beings, but also, does not take into account outliers (other factors).

“We hope that researchers will come to realize just how precarious a position we’re in when we’re trying to construct universal theories from a narrow, and unusual, slice of the population,” says Heine, as she further suggests journal editors and researchers discuss limitations (factors that may have been discovered when testing a hypotheses).

Thankfully, in my pursuit of Psychology, we were encouraged to disprove our findings. Our professors showed us the dark side of science and why it is vital to be mindful and critical of our research.

When asked to “prove” our theory, we needed to include studies that had been tested and researched over long periods (longitudinal studies) before we could begin to discuss the possibility of a “claim.”

But even then, when evidence was prominent, we had to endeavor to disprove and find evidence that contradicted our findings—that opposed our theory. So no matter how convinced we were about our theory (and trust me, I too would be convinced that my view was right), we had to criticize our own work and try to disprove ourselves to minimize falling prey to our biases and agendas.

As I learned about the importance of disproving myself, I realized that additional factors often needed to be examined and explored beyond the initial experiment. Moreover, it showed me how easy it is to fabricate or obscure findings and mislead people when we fail to include all results, even those that disapprove our theory or findings. For example, suppose there is enough evidence to make a solid and convincing argument, regardless of conflicting evidence or factors. In that case, this research can be used as concrete evidence to push an agenda or point of view—or even add a community of people to the D.S.M claiming they are abnormal due to their sexual preferences. Alarming, to say the least.

Accountability and disproving our beliefs in science and life take us out of the equation. It gets us out of the way of ourselves—our ego, our desire to find something new or revolutionary, our need to be right, our fears. It calls us to be diligent and weigh up all possibilities, rather than storm ahead in one direction, ignorant of essential factors that could minimize harm to others.

After a while, I became interested in disapproving my theories, as much as proving them, for I could find data and other perspectives and express a wholesome, well-rounded argument that also opened the door for others to share their insights—not dismiss them. This process instilled in me patience and being okay with sitting on the fence about things while I explore, question, and seek truth in its entirety. It’s also taught me the importance of putting aside my ego and eagerness for results that most likely would benefit me first or the most.

Often, scientists so desperately try to prove their theory and findings that they miss (or leave out) essential factors that contradict their conclusions or invite them to investigate further. And as we have seen, by acting too quickly, they become deceived by their desire to prove their theories.

The problem with being concrete in our beliefs is we can become blind and ignorant, and this is where we segregate ourselves from humanity, and division occurs. Furthermore, in these mindless pursuits, people may justify that this was in service of helping others—but to be of service requires humility and a hard look at ourselves, and our motivations, before acting. It also needs us to be open to others who view things differently and never to shame, put down, or be aggressive in our desire to convey a message.

But, people who think in opposition to the perceived “norm” are often alienated, cast out, or labeled “disturbed.”

In 1973, due to protests from L.G.B.T.Q. activists, the de-classification of homosexuality in the D.S.M. was ruled, alongside removing “Ego-syntonic Homosexuality.”

They acknowledged that being homosexual was not a mental illness, nor should they be labeled as “abnormal.”

The most alarming aspect of this world is the power given to a collection of individuals named “experts”—who can classify a population of people, like homosexuals, deeming them to have a mental disorder. And yet, we may read this and think how unjust this is while also participating today in the discrimination of others because we believe we are right and they are wrong.

What about in the future, when we come to find out our beliefs may also be wrong, or misconstrued, or shortsighted? Will we reflect with regret and sincere remorse to those we outcasted for not agreeing with us or who were wary about fast-tracking new findings and treatments—or will we dismiss it as another historical blunder?

As human beings with diverse experiences, cultures, and understandings, it is absolute nonsense to think that every one of us has to agree and that we cannot have a healthy debate without trying to top one another.

Where we become lost in our endeavor to bring change, implement new understandings, and have a healthy dialogue, is the delusion that we must sway one side to stand with us, and if they don’t, they are somehow wrong or abnormal. Isn’t this—gaslighting?

This is dangerous, not only for humanity as a whole but for ourselves, to be so convinced that our way is the only way and to put down others for not seeing our way. It is a sure path to foolishness too.

We must remember that those in positions of authority and scientific fields are also humans with their agendas, both good and bad, moral and immoral. A white lab coat, much like a priest’s robe, is not enough evidence of their trustworthiness and verification of a moral compass.

We do not have to trust external sources we do not know and cannot verify to the fullest. With everything, time, patience, and verification is needed for trust to be built, and the acknowledgment that there is a potential for the fallacy of science, just as there is misconduct in business, and dishonesty in relationships.

We can be at the mercy of people who are endeavoring to make scientific discoveries for their personal interests and motivations, who are quick to conclude findings to the detriment of human wellbeing.

Of course, many things we learn in life are through trial and error. But when it comes to speaking with authority and change that can impact the lives of others, we need accountability and patience; we need longitudinal studies that not only prove scientific findings but also endeavor to disprove to see beyond bias.

At times, the idea of discovering something new and being the first, or the biggest, or because of profit motivation, has been more important than saving lives and doing right by others.

I had learned and researched these “mishaps” in history long ago, but in my hope to include them in this article, it was a challenge to find such monumental points in history online. Why? Are these facts hidden away?

I came across this:

“Phases of intolerance have been fuelled by such fear and anger that the record of times favorable toward drug-taking has been either erased from public memory or so distorted that it becomes useless as a point of reference for policy formation. During each attack on drug taking, total denigration of the preceding, contrary mode has seemed peccary for public welfare. Although such vigorous rejection may have value in furthering reducing demand, the long-term offed is to destroy a realistic perception of the past and of conflicting attitudes toward mood alternating substances that have categorised our national history.” ~ David. F Musto

We must learn from our past, mistakes, and impatience, for it allows us to trek forward with integrity. But, unfortunately, as humans, we tend to want answers and conclusions now rather than seeing the value and wisdom in cultivating patience and due diligence.

We naively place our personal power and belief in systems to our detriment, forgetting that these same institutes have inhumanely experimented on humans for centuries because their opinions blinded them—they should not have such final authority over humankind.

On the contrary, we may speak ill-will of corporations, of science, of religion. Still, as the saying goes, “it takes two to tango”—and there are magnificent findings that have longitudinal studies and ongoing research to further our understanding in scientific fields.

In our quest to evolve, it is in our best interest to open ourselves to both sides, so we do not fall victim to our blind spots, and we respect our fellow human beings—even if they disagree with our worldview. If our desire is truth, then it is the truth that should matter, not who arrives first—patience is key.

~